From Daguerreotypes

to Cabinet Cards

Daguerreotypes, Ambrotypes, Tintypes, Cabinet Cards, and Carte de Visite

Before digital files and even film, photography lived on metal, glass, and cardstock. The early photographic processes weren’t just about capturing a likeness—they created physical, one-of-a-kind objects, often cherished, displayed, or passed down as heirlooms. Each format had its moment in the spotlight, and together, they tell the story of photography’s evolution.

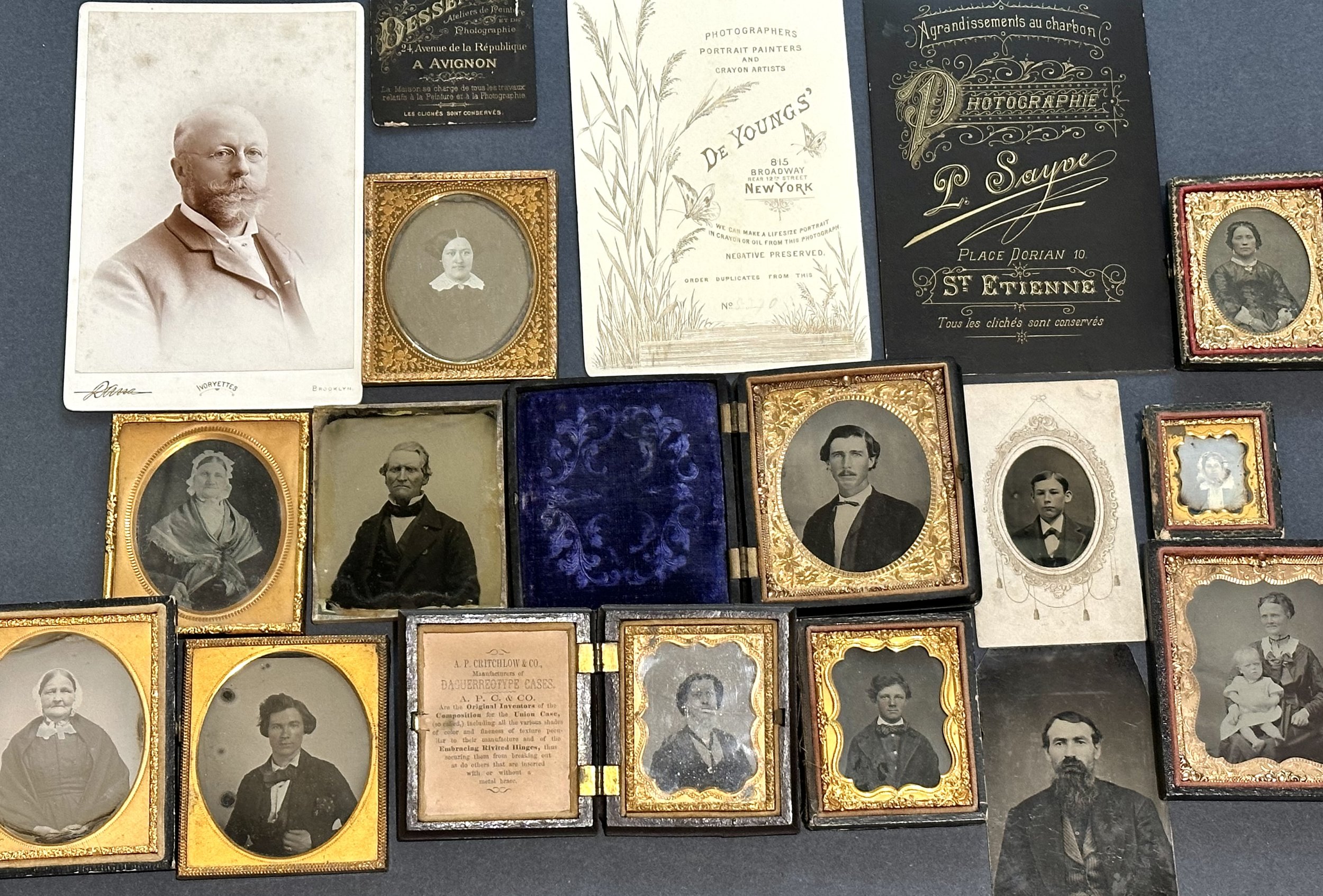

Daguerreotypes (1839–1860s)

The first publicly available photographic process, daguerreotypes were made on silver-plated copper sheets. They’re known for their mirror-like surface and incredible detail—so sharp they almost feel modern. Tilt one, and the image can vanish or appear depending on the angle, creating a ghostly, interactive effect. These portraits were often housed in ornate, velvet-lined cases.

Ambrotypes (1850s–1860s)

Created using the wet plate collodion process on glass, ambrotypes were typically backed with black material or made on black glass to turn the negative into a visible positive. The result is a softer, more delicate image than the daguerreotype, usually found in protective cases. Each one is a singular, irreplaceable moment.

Tintypes (1850s–early 1900s)

Tintypes, or ferrotypes, were made on thin sheets of iron, not tin as the name suggests. Faster and cheaper to produce, tintypes made photography more accessible. Often created at fairs or by itinerant photographers, they’re less formal and more spontaneous—sometimes even quirky. Despite their humble materials, many have stood the test of time remarkably well.

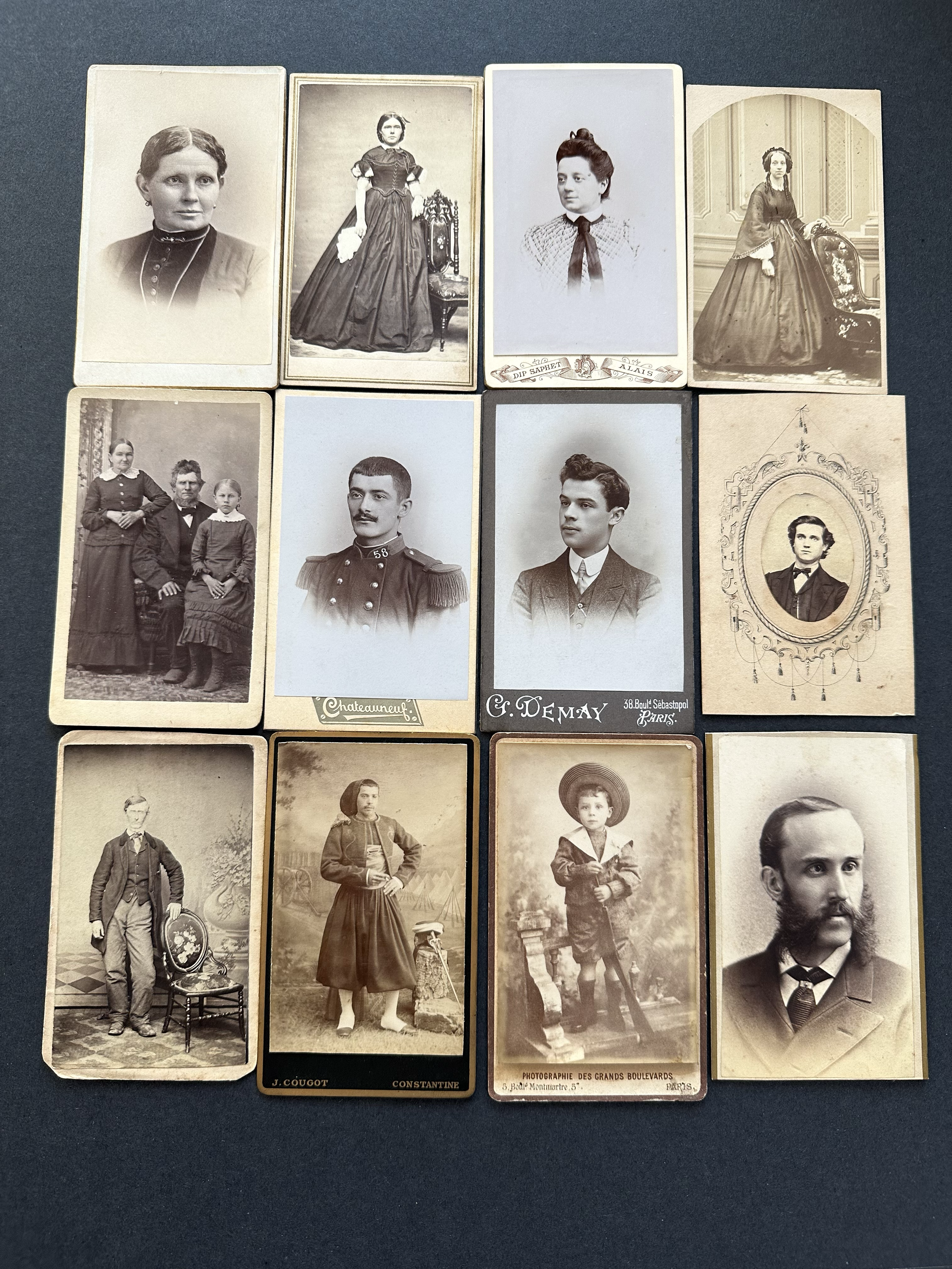

Carte de Visite (CDVs) (1850s–1880s)

CDVs were small albumen prints mounted on thin cardstock, roughly the size of a modern business card. Invented in France, they became wildly popular worldwide—especially for portraits of family, friends, celebrities, and even royalty. People collected them in albums, making them one of the first forms of mass-produced personal photography.

Cabinet Cards (1860s–1900s)

Cabinet cards were essentially larger versions of CDVs, offering more room for detail and allowing for full-body or group portraits. Mounted on sturdy cardstock, they were often used for formal studio portraits and displayed in parlors or family albums. Photographers used the extra space to showcase their studio names, logos, and decorative borders.

Each of these formats has a unique tactile and emotional presence. They aren't just photographs—they're historical artifacts, each one a portal to a different era. I love collecting and studying these pieces not only for their artistry and craft, but for the silent stories they tell through poses, clothing, props, and expressions frozen in time.

Daguerreotypes (1839–1860s):

Daguerreotypes: The First Photograph

The daguerreotype, introduced to the world in 1839 by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, was the very first photographic process made available to the public. Unlike modern prints or digital images, daguerreotypes were singular, one-of-a-kind objects, and each one is as unique as a fingerprint of the past.

What makes daguerreotypes so captivating is their mirror-like finish. The image is made on a highly polished sheet of silver-plated copper, which reflects light in such a way that the photograph often seems invisible from certain angles. Tilt it just right, and a strikingly detailed image of a person—often with piercing eyes and immaculate dress—appears as if summoned from the surface. Tilt it again, and the image can vanish into pure reflection.

Because the image forms directly on the metal surface without the use of a negative, each daguerreotype is entirely unique. There were no copies, no backups—what was captured was final.

Daguerreotypes are also extremely light-sensitive and fragile. Overexposure to light, moisture, or air can cause tarnishing or ghosting, which is why many surviving daguerreotypes are found sealed behind glass in ornate, velvet-lined protective cases. These cases weren’t just decorative—they were essential to preserving the image.

Due to the nature of the process, the subjects had to remain very still for extended exposure times, sometimes up to a full minute or more in the earliest years. Special neck and head braces were often used to reduce movement. As a result, daguerreotype portraits often appear solemn or intense—but not without incredible presence and detail. Every strand of hair, every texture in clothing, every glint in the eye—captured with remarkable clarity.

Daguerreotypes were at their height in the 1840s to early 1850s, before being surpassed by newer processes like ambrotypes and tintypes. Still, they remain a breathtaking and hauntingly beautiful window into photography’s birth—a silver mirror holding onto a moment more than 180 years old.

Ambrotype: Ghosts on Glass

Following the daguerreotype, the ambrotype emerged in the 1850s as a more affordable and accessible photographic method—yet no less enchanting. Made using the wet plate collodion process, ambrotypes involved coating a piece of glass with a light-sensitive emulsion, exposing it in-camera while still wet, and then developing the image immediately.

What makes ambrotypes special is that they are actually negatives—but when backed with black velvet, dark paper, or even painted black on the reverse side, the image appears as a positive. This creates a soft, ethereal quality that feels almost like a spirit caught in glass. Some were also made directly on black or dark glass, which eliminated the need for a backing, giving them a moody, striking richness.

Each ambrotype is a unique original, just like a daguerreotype, because there was no negative to make reproductions from. They were typically enclosed in small cases with a decorative mat and cover glass, not just to protect the fragile emulsion, but to elevate the portrait as a cherished keepsake.

Ambrotypes have a softer appearance than daguerreotypes—less metallic and reflective, more matte and moody. They often feel intimate and quiet, showing subtle emotion in the eyes and gentle detail in the fabric and backgrounds. With exposure times still requiring subjects to sit very still, the expressions tend to be serious, and sometimes haunting.

Though ambrotypes were eventually overtaken by tintypes and albumen prints, they remain an important chapter in photographic history—a poetic blend of chemistry and craft, where every face tells a story through the hazy shimmer of glass.

Tintypes: Iron Shadows of the Past

Following daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, the tintype also called ferrotype, emerged in the late 1850s as the next evolution in photography—offering a more affordable, faster, and rugged way to preserve a portrait. Despite the name, tintypes weren’t made of tin at all. Instead, they were created on thin sheets of iron coated with black enamel or lacquer.

Using the wet plate collodion process, photographers would coat the metal plate with a light-sensitive emulsion, expose it in the camera while still wet, and develop the image on the spot—often within minutes. This made tintypes especially popular with traveling photographers, soldiers during the Civil War, and at fairs or carnivals, where people could walk away with their portrait almost immediately.

What makes tintypes especially charming is their raw, often candid feel. Because the process was quick and relatively inexpensive, it captured a wider range of everyday people—children, couples, soldiers in uniform, and even pets—sometimes posing seriously, other times smiling or holding props.

The resulting image is a direct positive, appearing instantly as a finished photograph on the darkened metal surface. Unlike daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, tintypes were often uncased, slipped into paper mats or albums, or simply kept loose. Their durability meant they could survive rough handling, making them ideal keepsakes for loved ones far away.

While the clarity may not match that of a daguerreotype, tintypes have a special, almost gritty beauty. Their tones are rich and earthy, and their imperfections—scratches, flaking edges, faded corners—add to their character.

Tintypes remained popular well into the early 1900s, overlapping with more modern photographic prints. Today, they’re treasured as windows into everyday 19th-century life, full of personality, charm, and history etched in iron.

The Beauty of the Cases

Many early photographs—especially daguerreotypes and ambrotypes—were housed in beautifully crafted hard cases designed to protect the fragile image inside. These cases often featured a hinged, clamshell-style design, made from wood or a thermoplastic material like gutta-percha, and covered in leather, embossed paper, or ornate pressed patterns.

Inside, the photograph would be mounted behind protective glass, held in place by a delicately stamped brass mat and preserver frame—sometimes with intricate floral, scroll, or geometric designs that added elegance and richness to the image. The opposite side of the case was typically lined with lush velvet, often embossed with elaborate textures or patterns in deep hues like crimson, royal blue, or emerald green.

These cases weren’t just functional—they were decorative heirlooms, meant to be held in the hand and admired. Over time, the cases became as collectible as the images themselves, with variations in design, material, and mat styles helping to date and identify the photographs they once held.

Tintypes, while more often housed in simpler paper sleeves or albums, were occasionally placed in similar cases, especially in their earliest years or when the photograph was of particular importance. When you find a tintype in one of these velvet-lined brass-matted cases, it’s a treasure—both photograph and presentation woven together into a single object of 19th-century craftsmanship.

Cartes de Visite (CDVs): Calling Cards in Photographic Form

The Carte de Visite, or CDV, was a small photographic print mounted on cardstock, about 2.5 x 4 inches in size—roughly the dimensions of a modern business card. Invented by French photographer André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri in 1854, CDVs became a massive global phenomenon in the 1860s and 1870s, ushering in one of the earliest forms of mass-market photography.

Using the albumen print process, photographers would create a negative on a glass plate and then produce multiple paper prints, which were mounted onto pre-cut card stock. This allowed for affordable duplicates of portraits—so families and friends could share photographs just like they might share letters or calling cards.

CDVs often featured studio portraits of individuals or families, posed with props, elaborate backdrops, and formal attire. But they weren’t limited to just personal photography—people also collected CDVs of celebrities, royalty, political figures, and even military generals. Albums were produced specifically to house these treasured little images, and collecting them became a cultural trend.

CDVs also played a key role during the American Civil War, allowing soldiers to send images home to loved ones—and vice versa. Some included printed photographer information or ornate studio logos on the reverse, which now help modern collectors identify origin and date.

While they were eventually overtaken by larger cabinet cards in popularity, CDVs remain an important and charming piece of photographic history—small snapshots of the past that reflect not only the people, but the cultural values, fashion, and photography styles of the time.

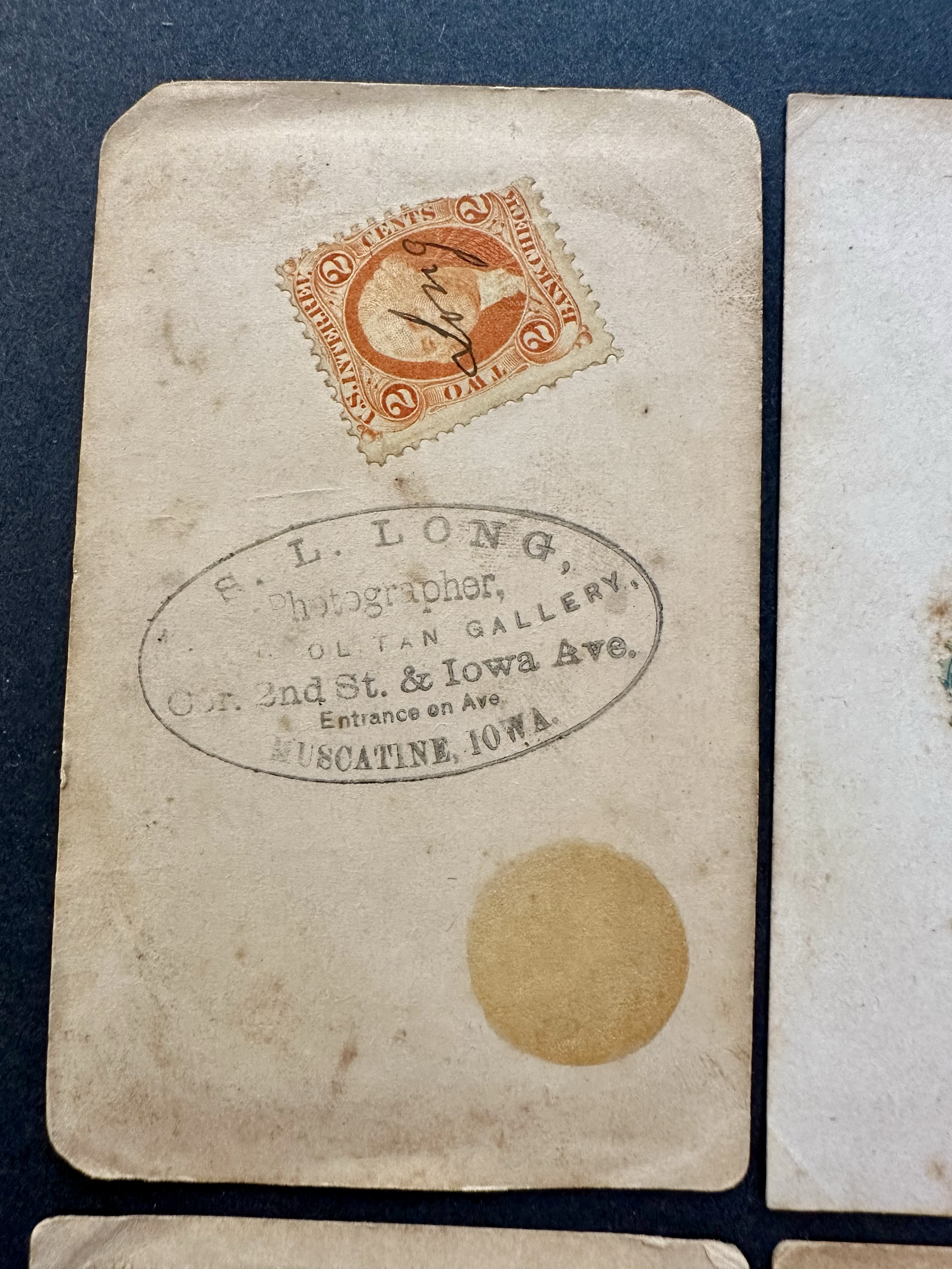

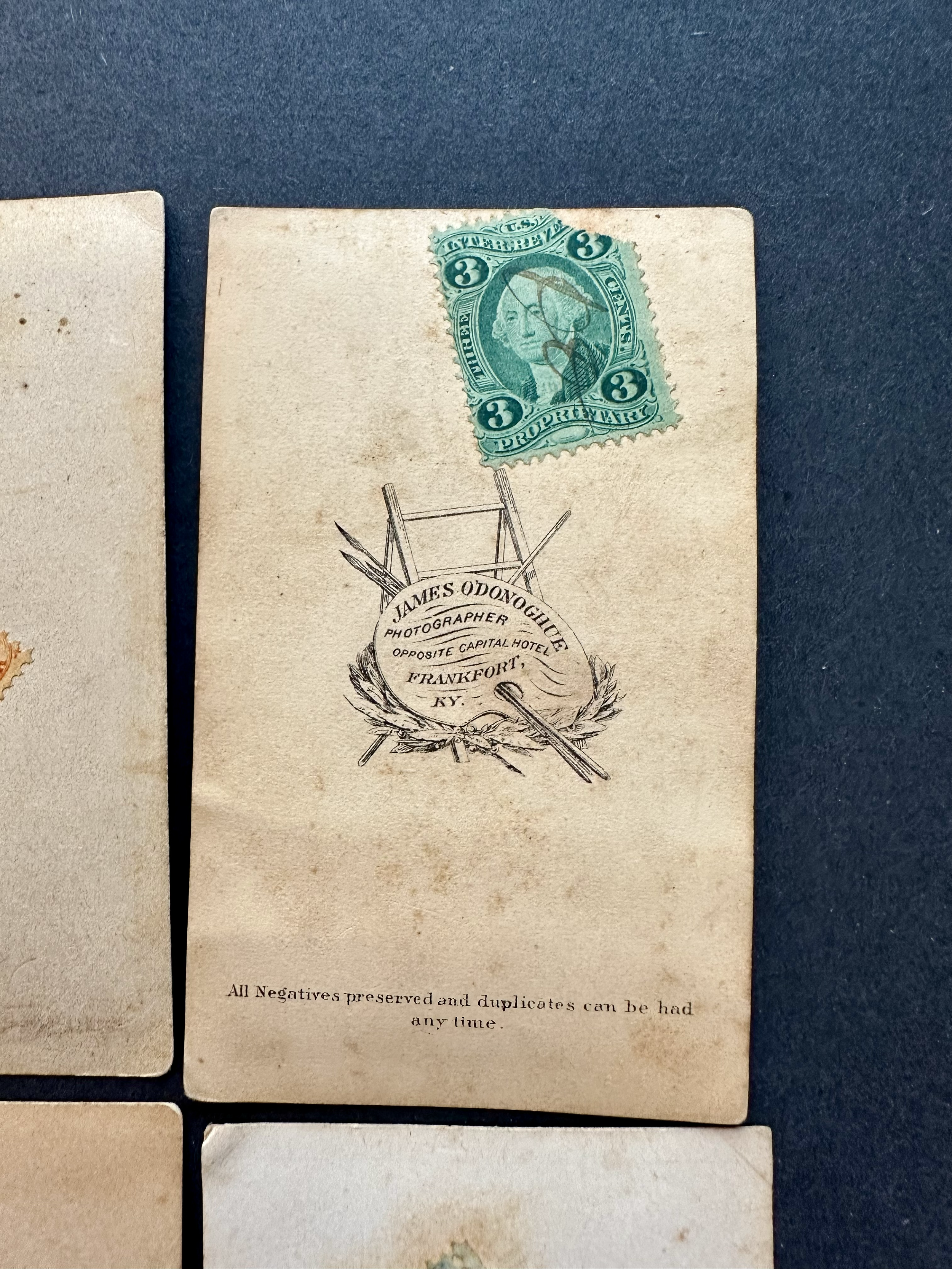

Civil War Tax Stamps: A Forgotten Footnote on the Back of CDVs

One of the most intriguing historical details found on some Carte de Visite (CDV) photographs and some mounted tintypes—especially those produced and mailed between 1864 and 1866—is the presence of a revenue tax stamp affixed to the back. These small, colorful stamps weren’t just decorative; they were part of a federal tax effort to help fund the American Civil War.

In 1864, the U.S. government passed a law requiring that photographs sold for profit—which included those commissioned in studios and often exchanged or mailed between family members—carry a revenue stamp. The cost of the stamp depended on the price of the photograph, and they typically ranged from 1 to 5 cents. Once affixed, the stamp would be canceled by the photographer, either with a handwritten date or initials, or occasionally with a studio handstamp.

These stamps served a dual purpose: raising money for the Union war effort and creating a form of regulation over the increasingly booming photography business. The tax was in effect only for a brief period—from August 1, 1864, to August 1, 1866—so finding a CDV with an original tax stamp still attached is not only a rare treat, but also a helpful tool for dating the photograph within a very specific window in history.

Photographers often placed the stamp on the back of the CDV, and it's not uncommon for collectors today to find beautifully preserved examples, complete with cancellation marks that act like little signatures from the past. These tax stamps offer a deeper connection to the political and economic context in which early photographs were created and shared. They’re a reminder that even the most personal of objects—like a cherished portrait—can carry the imprint of a nation at war.

For collectors and historians alike, a tax-stamped CDV is a compelling artifact, representing the intersection of personal memory, commercial art, and national history.

Cabinet Cards: Portraiture at Its Grandest

Cabinet Cards were a popular form of portrait photography in the late 19th century, particularly from the 1860s to the 1890s, and they are often considered a successor to the Carte de Visite (CDV). While CDVs were small and portable, Cabinet Cards were much larger, typically measuring 4.25 x 6.5 inches—about the size of a small book or a large photograph. This larger format allowed for greater detail and elaborate studio settings, making them a favored choice for more formal portraits, especially family and professional images.

Photographers who specialized in Cabinet Cards often used larger cameras with more advanced techniques compared to those used for CDVs, resulting in higher-quality prints that showcased the intricate details of the subject's clothing, hair, and expressions. The subjects of these portraits—whether individuals, families, or groups—were usually posed in a more stately, refined manner, often with elaborate backdrops like draped curtains, ornate furniture, or painted scenic landscapes that conveyed wealth and status.

Much like CDVs, Cabinet Cards were often mounted in albums or displayed on mantels or tables. They became a fashionable way for families and individuals to preserve important moments—especially formal events such as weddings, graduations, baptisms and first communions or significant milestones. Over time, the Cabinet Card format became synonymous with the "professional" portrait, marking an era when photography transitioned from something experimental to a widely accessible, important social practice.

Today, Cabinet Cards remain a highly collectible form of early photography. Their larger size, fine details, and historical context make them not only valuable as artifacts but also cherished as windows into the past, offering a glimpse into the lives, fashion, and societal values of a bygone era. Whether with ornate, hand-painted borders, studio-imprinted logos, or elaborate poses, Cabinet Cards represent a high point in portrait photography, an art form that continues to captivate collectors and history enthusiasts alike.

The Intricate Details of CDV and Cabinet Card Backs: Studio Markings and Artistic Flourishes

While the front of a Carte de Visite (CDV) or Cabinet Card captured the subject’s likeness, the back of the card often held just as much interest, showcasing the photographer’s studio information and sometimes an entire work of art. The back served not only as a functional means of providing contact information but also as a signature piece that highlighted the photographer's branding and artistic flair.

For both CDVs and Cabinet Cards, the photographer’s name, studio location, and business details were often printed in intricate letterpress typography or engraved into the card. Many photographers added decorative flourishes, borders, and even illustrations that reflected the personality and style of the studio. These back designs helped to brand the studio, making it recognizable to clients and visitors. Some even included prices, services offered, or mottos to reinforce the photographer’s artistry.

The backs of Cabinet Cards, which were a larger format than CDVs, often featured even more elaborate designs. Some included embossed or stamped information, while others had full-color illustrations or scenic views, sometimes incorporating victorian-era floral motifs, scrollwork, and geometric patterns. The backs of these cards became canvases for some photographers to really showcase their artistic style, making each card not just a photograph, but a piece of art in itself.

The intricate designs on the backs of both CDVs and Cabinet Cards served as a way for photographers to distinguish themselves in an increasingly competitive market. For collectors, the backs of these cards can often hold as much historical value as the front, offering insight into the cultural significance of the time and the photographer's clientele, location, and business practices.

These backs also play a key role in identifying the age of the photograph, as certain studio marks, logos, and printing styles can help date the card or even pinpoint a specific photographer from a particular city or region.